I’m 66 years old. That’s 66 birthdays, 65 Christmases, 65 Father’s Days (35 as a father), etc.

I’m 66 years old. That’s 66 birthdays, 65 Christmases, 65 Father’s Days (35 as a father), etc.

Eventually, you get to a place where you pretty much have everything you want that’s within reason. (This, of course, excludes the Tesla [do they make a minivan? I really like minivans], the Can-Am Spyder, the boat, the summer house on the lake, etc.)

All of which makes for frustration and anxiety as my children and my wife try to buy presents for me.

But, somewhere in my early 30s, when my parents were still alive, I got a brainstorm (one of the few that did NOT turn out to be just a rainstorm). An idea for a gift for my dad.

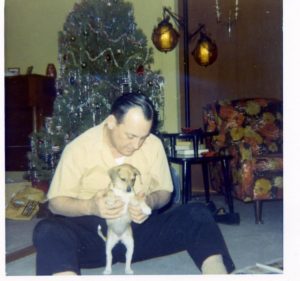

My father, John A. Moody, Jr., was a member of what we’ve come to call the “greatest generation.” He had lived through the depression (as a baby), served in WWII (as a young man), and worked hard the rest of his life to feed and raise a family of four. He was determined that his children would have a better life and better opportunities than he had ever had.

But at about the age of 60, he had been diagnosed with cancer, which chipped away continually at his few remaining years. He then had a stroke, and eventually succumbed to the cumulative effects of these afflictions.

Dad had been a hard worker, struggled through rough economic times, and managed to shield his family from the impact of most of those struggles.

I think every parent second-guesses their parenting decisions as they enter their “sunset years.”

Did I really do the best I could?

Could I have done better?

Did I give my kids the best of life that I could afford?

If I’d done better, would they have a better life and a brighter future?

And I’m sure my parents were not exceptions to that rule.

So, my idea was simply this:

I would write a letter to my dad, thanking him for all the things I had learned and gleaned from him, and giving examples of how those things were impacting my life. I would quote back to him those sayings and phrases I heard every day of my life – phrases like “Anything worth doing is worth doing right.” I would encourage him with the knowledge that he had successfully transferred to me the best of his accumulated wisdom, and that I was a better man because of it.

I entitled the letter, “One Father’s Legacy.” And I sent it to him for his birthday. He read it and cried. That same year, my sister sent him a collage of all the wonderful attributes she saw in him, and the characteristics of his personality that made him who he was.

My mother said that those gifts meant more to him than anything else we could have given him.

My father died a poor man, heavily indebted. But he left a rich legacy to his children in so many ways, and I’ve never regretted taking the time to tell him so.